Few periods in American history have shown greater economic prosperity than the post-World War II boom. The United States had emerged as the manufacturing powerhouse of the world, and as the global hegemon, it held most of the giants of international capital right within its borders. However, this was also an age of great skepticism of the American system. There was plenty of content and cartoons helping push pro-American sentiments.

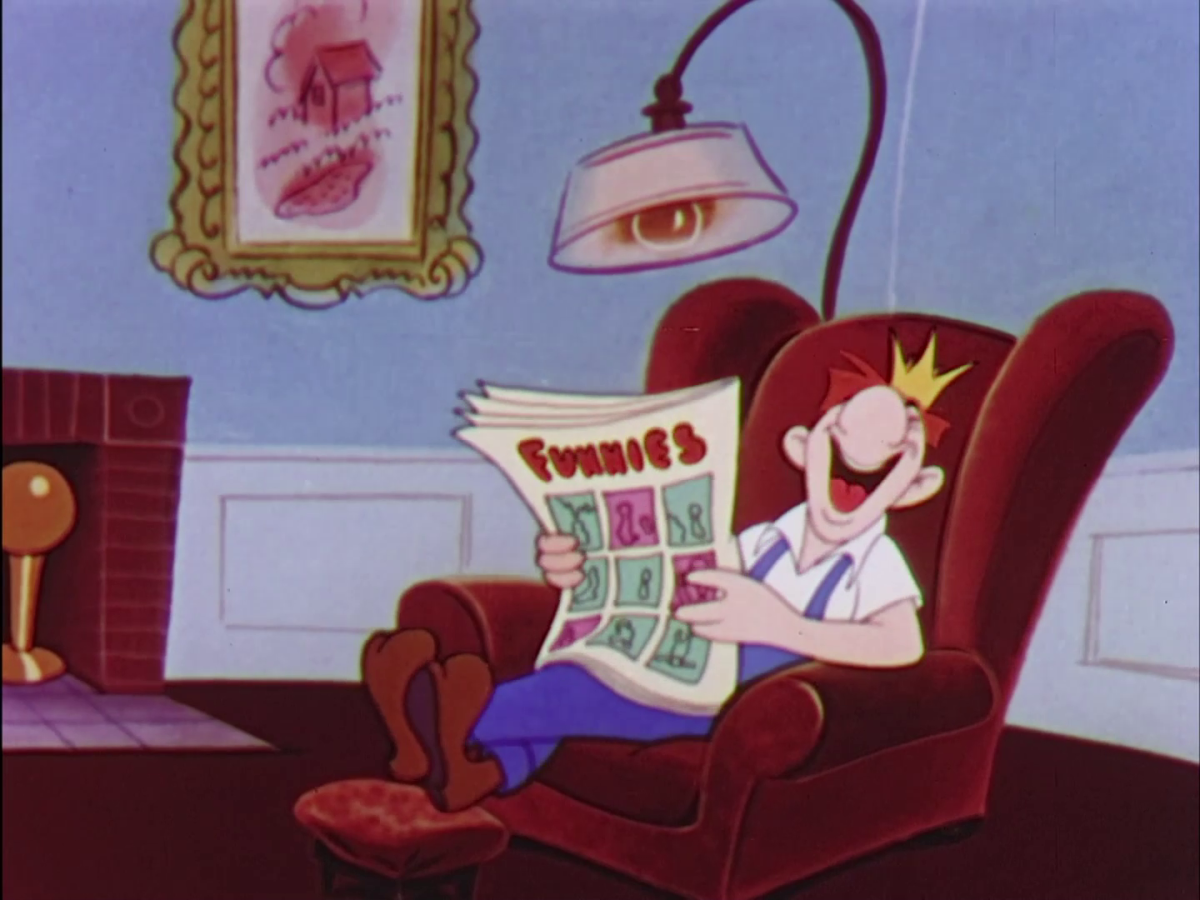

One pro-capitalist cartoon from 1949—Meet King Joe—attempts to explain and justify that success. I want to explore what this short film says, what it leaves out, and why, ultimately, it serves as an unapologetic endorsement of American imperialism.

Before reading, I recommend watching the cartoon—it’ll make the argument clearer.

⸻

The Setup: “King of the Workers of the World”

The film follows a narrator and an average American factory worker named Joe. The narrator hails Joe as “the king of the workers of the world,” mainly because, as he explains, Joe has it much better than workers in the global South, and even in other imperial core countries—simply by virtue of being American.

Joe lives in a comfortable home, has access to medicine, food, leisure, and strong purchasing power. The film insists this isn’t due to racial or religious superiority, but instead because of “the American way of doing things.”

To explain this, the cartoon compares Joe to his grandfather, who worked grueling hours producing goods by hand in the past. Joe, by contrast, uses advanced machinery, works fewer hours, and earns more—because he produces more value per hour. That’s what, according to the narrator, makes Joe’s labor “worth more” than his counterparts overseas.

Joe questions this narrative, pointing out that his grandfather’s shop was closed down because his shop used horse carts which could not compete with automobiles. But the narrator quickly reassures him: Joe’s grandfather got a better-paying factory job with shorter hours.

This is presented as a happy ending—a win for “progress” and innovation. Even if some people lose out temporarily, the film argues, competition drives innovation, which ultimately benefits everyone.

The narrator also briefly touches on the American stock market. He claims that because Americans invest in public corporations, the promise of profit drives technological advancement and economic growth.

But beneath all this capitalist optimism lies a glaring omission.

⸻

What the Film Ignores

The cartoon compares Joe’s life to that of a gasoline transporter in 1940s China. It claims that because China lacked infrastructure, Chinese workers couldn’t generate as much value, and were therefore paid less.

Here, the film begins to show its ideological core. It never asks why China was so underdeveloped. It conveniently ignores the historical context: a monarchy that resisted industrialization, a violent regime change, a long civil war, a brutal Japanese occupation, and further civil unrest. The cartoon glosses over this entirely, failing to mention centuries of imperial exploitation and political chaos.

Near the end, the film showcases statistics (outdated today, but still revealing of its mindset): despite making up only 7% of the world’s population, Americans owned half of all the world’s radios, 54% of its telephones, and 72% of its automobiles. They had 92% of the world’s bathtubs, and basically every refrigerator that exists. The message is simple: American capitalism works. It’s the best system ever created, and its results speak for themselves.

The film concludes by declaring that the manager, the worker, and the owner make “the best team the world has ever seen”—a trio responsible for making America the “industrial master of the world.”

⸻

The Hidden Message: Imperialism Works—for Some

Let’s take a step back. Meet King Joe is a 10-minute cartoon aimed at skeptical Americans who may sympathize with working-class struggles at home or abroad. Joe is portrayed as a regular guy with doubts. He resents how his grandfather lost his business, and is skeptical of the ultra-wealthy. He seems to relate to other working people around the world.

But the narrator’s job is to correct Joe—to show him that his relatively high standard of living is not only because of, but dependent on maintaining the American-led global system.

And here’s where the cartoon becomes propaganda.

Joe thinks he’s part of the global working class, or proletariat. But in reality, he’s part of what’s called the labor aristocracy: a privileged group of workers in first world countries whose material conditions are subsidized by imperialism. His job is easier, and pays better, not because of American innovation alone—but because the United States extracts cheap resources and labor from the global South.

Joe isn’t part of the capitalist class—but he benefits from the global system they control. His interests, whether he knows it or not, lie in protecting that system. That’s why the narrator calls him “King of the Workers of the World.” He’s not a ruler, but he’s treated like one—by virtue of his national citizenship, not his class.

⸻

Why It Still Matters

In 1949, America was at the height of its global power. But in many ways, the message of Meet King Joe still resonates today. The American economy has changed—there’s less manufacturing, more service jobs, more inequality—but the basic reality holds: much of the American middle and lower-middle class still benefits from global systems of exploitation.

And that reality creates a challenge for international solidarity.

Many first-world workers, rather than fighting to dismantle imperialism, instead seek better inclusion within it. They want higher wages, cheaper goods, more representation—but not fundamental change. That is where the global workforce divides.

The fact of the matter is that both mine, yours, and Joe’s class interests are the same as that of American Empire. Unless first-world workers are willing to fight against their own material interests, they remain class enemies of the global proletariat.

Meet King Joe might be a cheerful cartoon on the surface. But underneath, it’s a calculated endorsement of empire. And it reminds us: if you want to fight for real liberation, you’ll have to face an uncomfortable truth:

Sometimes, justice means giving something up.