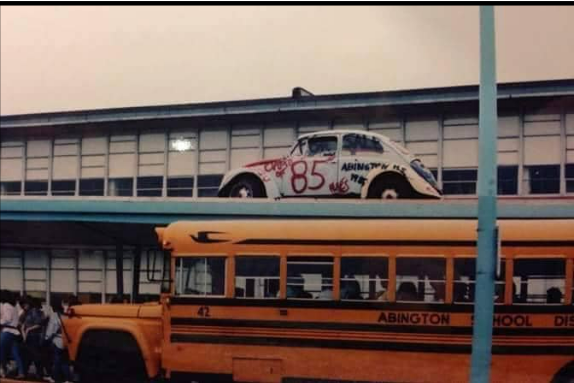

Thirty-four years ago, at the Abington Centennial Event which celebrated 100 years of the Abington School District, a time capsule was placed somewhere in the ground. Although spectators must have been there in 1988 to witness this burial, there was obviously no post on social media to memorialize the event. In fact, the photos (if they were taken) must exist only as prints and may be yellowing on the dusty pages of someone’s scrapbook.

But that Centennial event in 1988 was the last time anyone ever saw this time capsule. Where is it buried? What is in it? No one fully knows. The Abington Senior High time capsule is a mystery that has yet to be solved.

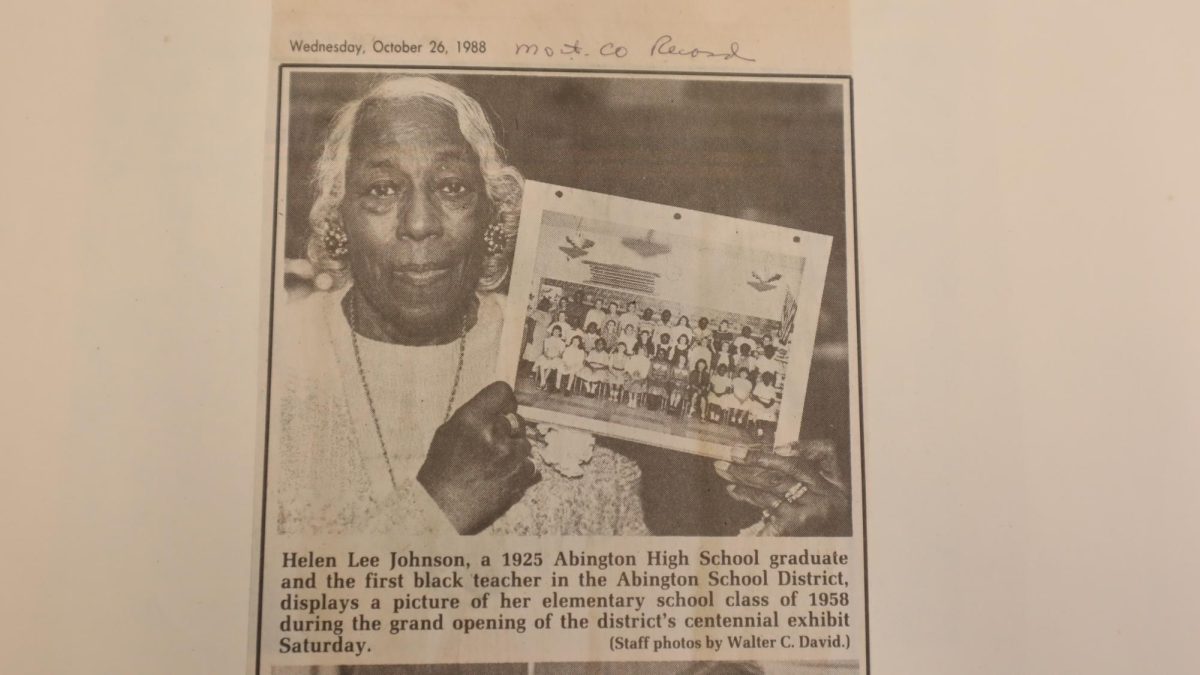

About two years ago, I became fascinated by Abington’s history. The Abington School District has existed since 1888, and some artifacts are over a century old. As I entered the aging Archives filled with brittle pages and forgotten items, I took a seat in front of the many yearbooks that date back to over a hundred years ago. It’s astonishing and humbling to flip through the pages of a 100-year-old Oracle yearbook and see the faces of students from those times. One of the things that amazed me as I looked at those faces was that there were some African American students who appeared on those pages decades before the Civil Rights Movement. And one of those students was Helen Lee (class of 1925).

We can’t talk about the time capsule without discussing the remarkable Helen Lee, an Abington alum and later the first black teacher in the Abington School District. I did a little digging about her and learned that after graduating from Abington, she went on to get her bachelor’s degree in Education from Cheyney University in the late 1920’s. I wanted to learn more about her and what life was like at that time, so I went straight to a primary source. My great-grandmother was born in 1927, and she told me that most women didn’t go to college when she was growing up. When I searched for more information, I learned that only 7% of college students were women in 1920. The numbers steadily increased after the 19th Amendment was passed, and the number of women attending college then grew.

Still, Helen Lee was a black woman. She was definitely a first-generation college student before that term even existed because, according to census records, her father was a steel mill laborer. I wanted to find her yearbook picture from Cheyney; however, when I searched for it, assuming she graduated in the late 20s, I discovered that Cheyney had a different name during that period and an intriguing history. A silversmith named Richard Humphreys, originally a slaveholder from the West Indies, relocated to Philadelphia in 1764. Humphreys was a Quaker concerned about the struggles faced by free black people in earning a living. When Humphreys died in 1832, he left $10,000 to create an institute whose mission was “to instruct the descendants of the African race in school learning…to qualify them to act as teachers.” Originally called the Institute for Colored Youth, in 1837 this school became the first college for black Americans. The school was eventually relocated from Philadelphia to Cheyney, and in 1914, the school’s name was changed to the Cheyney Training School for Teachers. This was where Helen Lee attended.

Although I was unable to find any yearbook from her time there, I managed to locate some newspaper articles. At the commencement in 1930, Dr. Leslie Pickney Hill spoke: “It is Cheyney’s purpose to help us of a minority group more effectively develop a culture within a culture.” This idea most likely stemmed from the concept of what W.E B. Du Bois termed “the talented tenth” in 1903. Du Bois emphasized the importance of promoting leadership through higher education (rather than just technical training) to the top 10 percent of black Americans.

Helen Lee Johnson returned to the Abington School District from 1930 to 1966. She taught at the Park School, built in Crestmont in 1901 and closed down in 1966, where she had attended as a child. I wanted to know more about her experience and her story. What was Abington like in the 1920s and what was it like to teach in Abington at that time?

Very little was written about Helen Lee Johnson; however, I found something in the Philadelphia Inquirer from 1988 about the 100 year anniversary of the Abington School District. Helen Lee Johnson was featured in one of their stories about the district’s Centennial celebration, and she said that a video recorded interview was conducted with her and placed in the time capsule at the event. The article said that the time capsule was buried in 1988 with the plan to apparently unearth it in 2038 at the 150th anniversary of the school district.

Here’s the mystery. Her video-recorded interview (most certainly on VHS tape) was buried in a time capsule. I asked our school’s archivist if there was a copy of this videotape or if the only copy was inside the time capsule. He said that the only copy is inside the time capsule.

So, the time capsule became a wormhole for me. I asked around and no one seemed to remember anything about a time capsule. I searched through newspapers. I went through alumni newsletters. I reached out to the class of 1988 on Facebook. I went through yearbooks from the late 80’s and early 90’s to see whether teachers might still be around and remember something about this time capsule. My main question: Where is it buried? My other question: Why is this not on anyone’s radar?

I didn’t stop there. I contacted the Superintendent, who started contacting people who might know. Someone had to have been at the Centennial Event in 1988, but I quickly learned that 34 years is a long time. The people who are still at the school from “back in the day” didn’t necessarily attend that Centennial Event when they buried the time capsule. So, this got me wondering about time capsules in general. Who came up with this idea of putting items in the ground and burying them for the future?

According to the Smithsonian Institute, the oldest known time capsule in the United States was created in Massachusetts in 1795 by Samuel Adams and Paul Revere. It was discovered during a renovation of the state house in 2014. It can be argued that this wasn’t actually a time capsule, because there was no planned opening date; however, the contents were obviously buried for a future generation to discover– newspapers from the time, some coins- including a pinetree shilling from 1692 (minted in defiance of the British parliament in Massachusetts), and a silver plate with the date the capsule was buried July 4, 1795- 20 years after America’s independence.

But how many times have time capsules been buried and never found? The answer is…a lot. Although the idea of a time capsule seems like a great way to preserve history for future generations, there is a fundamental flaw with putting artifacts and treasures into the ground to be forgotten for decades: they are usually buried by people who won’t be alive to remind anyone when it’s time to open them. Believe it or not, most time capsules often get lost, stolen, or disconnected from the future.

According to the International Time Capsule Society in Atlanta, most of the world’s 10,000 time capsules are lost or forgotten. In 1991, this society released the 10 most wanted time capsules. Among these missing time capsules are:

The MIT Cyclotron Time capsule.

A group of engineers buried a time capsule in 1939, planning to unearth it 50 years later. But over time, the time capsule was forgotten, and in the meantime, scientists built a cyclotron particle accelerator with a 36,000-pound magnet in that very location. Although perhaps a great site marker, the cyclotron is impossible to move and the time capsule remains buried.

The original cornerstone of the U.S. Capitol.

The custom of burying time capsules is in part based on Masonic cornerstone-laying ceremonies. Masons frequently officiate rituals involving the placing of artifacts inside the cornerstones of buildings for later unearthing. George Washington supposedly enacted such a ritual in 1793 when laying the original cornerstone of the U.S. Capitol. While the Capitol has been remodel and reconstructed over the years, the original George Washington cornerstone has never been found. No one knows what, if anything, lies inside.

The time capsules of the city of Corona.

In Corona, California…there were a collection of 17 time capsules that dated back to the 1930s. Efforts were made to recover the capsules in 1986, but unfortunately, they were not found. “We just tore up a lot of concrete around the civic center, “said the chairman of the town’s centennial committee. Because of this, the town is actually the ‘record holder in the fumbled time capsule category’ with 17 time capsules buried – and lost.

If the time capsules themselves do not get lost, the content in time capsules often get damaged or destroyed. In 1931, when the Empire State Building was completed, a time capsule was deposited in the basement. When it was exhumed 50 years later, it was filled with water – the contents had dissolved. This is not uncommon. Most time capsules, if found, have suffered significant water damage. The longer they have been buried, the more damaged the content.

Which brings me back to the elusive Abington Centennial time capsule. If we locate that time capsule, we may need more than just a VCR to be able to view that video cassette of Helen Lee Johnson. VHS deterioration of 10–20% occurs over a period of 10 to 25 years. VHS tapes that have been kept in a climate-controlled setting may have a slightly longer lifespan, but I don’t think a hole in the ground counts as climate-controlled. The sooner magnetic memories are converted to digital, the better.

The scientists who created the Golden Record on the Voyager spacecraft in 1977 knew this all too well. They actually created a 12-inch gold-plated copper disk, encased in a protective aluminum jacket with a cartridge and needle, with symbolic instructions that explain the origin of the spacecraft and how the record is to be played. The record has 115 images from earth encoded in analog form along with spoken greetings in many languages both ancient and modern. There is a collection of sounds from earth and a 90-minute diverse selection of music. The now late astronomer Carl Sagan had spearheaded this project and explained that although it would be forty thousand years before the spacecrafts reach any other solar systems, “The record [will be] played only if there are advanced…civilizations in interstellar space. But the launching of this bottle into the cosmic ocean says something very hopeful about life on this planet.”

Maybe hope is the beauty of time capsules. Hope that someone will remember and care that our lives mattered and that our collective time together had meaning. I think that is why the Archives pulls me in and those old yearbooks keep me turning pages.

So for this reason, I am putting it out there to the Abington community. Someone out there knows where the Centennial time capsule is buried…let’s find Helen Lee Johnson’s videotape and whatever else might be stored inside.