Imagine you walk into someone’s birthday celebration with big letters “50’s Party” draped over the door frame. Do you imagine the guests to look a certain way– probably with the laces of their saddle shoes tied into bows and pink poodle skirts billowing at their sides? Now do the same thing again, but imagine that the “50’s Party” now reads “80’s Bash.” The subdued pinks of the guests’ outfits will most likely turn to neon-colored spandex outfits accompanied by manes of teased hair. Once more, keep the party sign visualized in your mind, now with the words, “ 2020’s-themed Party” plastered on. Is this visual slightly more difficult to create in your mind?

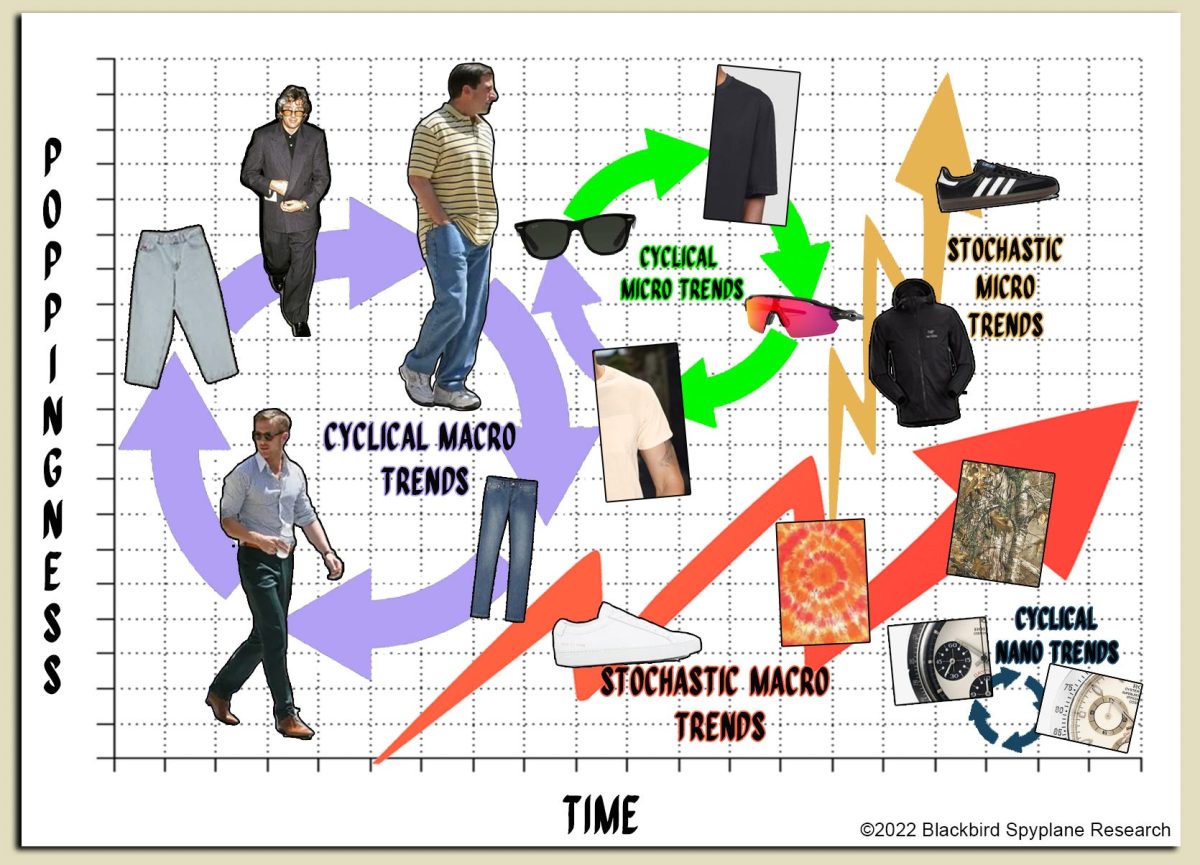

As I tried to conjure this image, I came up with no ubiquitous look that sums up the decade and couldn’t quite figure out why. Though I thought at first this might only be because it’s difficult to have perspective on the era you’re currently living in, I soon realized that my inability to come up with a style of the era could be attributed to so much more, specifically the rapidly changing standards of social media.

When something begins trending on a platform like TikTok, it usually is not implemented because of the general look or silhouette of the look, but rather to promote a product. Though this claim may seem inaccurate at first, think back to the latest trends you’ve seen on social media. The “preppy” aesthetic which entails a closet of Lululemon, Stanley cups, and Sol De Janeiro products and the infamous “Vsco girl” era of 2020 drove the sales of Hydroflasks and puka shell necklaces through the roof. These trends, like many others, were implemented by brands for the sole purpose of promoting their product and increasing growth in sales. In the uncommon case that a trend does go viral simply for the appeal of the “aesthetic” rather than marketing a product, the nature of TikTok leaves viewers consistently yearning for any inkling of new stimulation to provide them the hit of dopamine they so deeply desire. It’s become nearly impossible to sustain these insatiable viewers on a single trending style for even a month, let alone a decade.

Though this phenomenon of faster trend cycling is compelling, it holds much more meaning in our current society than simply a captivating topic of discussion. When trends cycle quickly, the fast fashion industry puts out low-quality, cheaper products in unethical ways to meet the public’s quickly changing needs. Though these products satiate the consumer’s immediate desire for a product, the items are soon discarded as a new batch of trends emerge. The resulting process is one that both exploits workers and emits inconceivable quantities of pollution. Trends die, and along with them, so do poorly made clothes. To end this cycle, the public must focus on buying long-term staples they enjoy and not mindlessly follow the crowds.