Studio Ghibli is a Japanese animation studio hailing from Tokyo and co-founded by Hayao Miyazaki. The distinct animation style of most of their films paired with insightful themes and strong characterization sets them apart from other animation studios, as their work has a universal appeal that transcends age demographics.

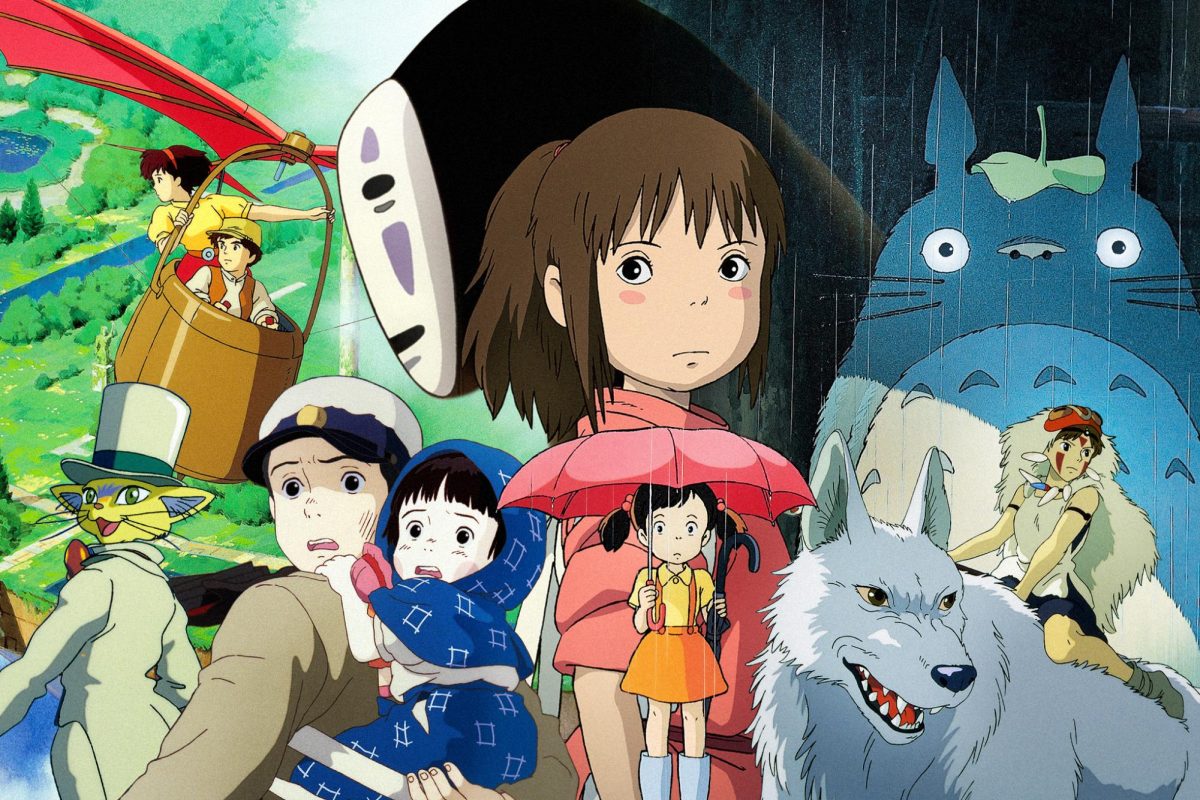

While I never experienced the magic of Studio Ghibli films as a child, I feel incredibly lucky to have discovered the movies in my teenage years. Three years ago I began my journey with Howl’s Moving Castle (which is by far my favorite), and ever since I have been making my way through the Studio Ghibli canon. After my first, I have watched Spirited Away, Kiki’s Delivery Service, My Neighbor Totoro, Ponyo, and most recently, The Secret World of Arrietty. All of these movies have distinct purposes, messages, and audience, yet their similarities create a unique and immediately recognizable style many regard as timeless.

One of the most important continuities present in any Studio Ghibli film is the importance of relationships on characters’ wellbeing. It is the friends, allies, and family members of the main characters who aid them most in overcoming challenges, contrary to the individualistic, lone-wolf messaging common in western cinema. Supporting characters are nothing new, yet it is the idea that a person cannot survive and eventually thrive without a strong support system that is so poignant across the entire franchise. The main child characters in Ponyo come to mind as a significant example of this. A young boy, Sōsuke, rescues the titular character, Ponyo, after a storm hits his seaside village. Ponyo heals a wound Sōsuke developed while saving her, transforming her from a fish to a human. From there, the characters develop an inseparable bond that encapsulates the sweetest form of platonic love only found in young friendship. The scene of their first meeting illustrates a crucial part of the Studio Ghibli philosophy: that the best friendships are equally reciprocated and help both members heal and grow as people in ways impossible without the presence of the other.

Focus on the sort of imagination only present in childhood is another significant motif in the Studio Ghibli universe. The plots of Spirited Away, The Secret World of Arrietty, and My Neighbor Totoro all hinge upon the concept that children possess a unique perspective on the world that is far more fantastical than the world of adults, and is lost when one grows up, yet their perspective is no less real than that of adults and often turns out to be truer than theirs. This idea contributes significantly to the timelessness and nostalgia characteristic of the franchise. An adult audience is able to relive the experiences of a childhood with so much brightness and mysticism that makes one realize how much is often lost in the transition to adulthood, particularly when an adult loses sight of the elements of life that children prioritize and adults forget. The Secret World of Arrietty highlights a common trait found in Studio Ghibli antagonists. Haru, the housemaid, is concerned with keeping the house clean and the ill protagonist, Shinto, in bed at all times, to an obsessive extent. She is ultimately the one to force the miniature, fairy-like characters living in the house to leave their home under the floorboards after she kidnaps the mother and calls a pest company to exterminate the rest of the family. Haru does this because she is too caught up in the worries of the modern world and therefore endangers the innocent lives of the small creatures she cannot see.

By contrast, Studio Ghibli also portrays the struggles and joys in adolescence as slightly older characters find their way in the adult world. In Kiki’s Delivery Service, Kiki leaves home at thirteen to establish herself in another city as a witch. She eventually finds a supportive community of people who all help her grow as a person in different ways. This film contains a scene that expertly tackles the concept of burnout, in which Kiki is no longer able to fly, and feels frustrated and depressed. A slightly older resident of the forest, Ursula, likens Kiki’s feelings to artist’s block and suggests that she rest, and find purpose in order to regain her flight. This scene sends a message that one can emerge from a challenge whole again, and better than before. Howl’s Moving Castle tackles aging literally as teenage protagonist, Sophie, is cursed and transformed into an old woman. Her curse is a reflection of Sophie’s own insecurities, and she gains confidence as the pressure of being a teenage girl dissipates and she is no longer held to the high standards of being a young person by society. Sophie’s curse is eventually broken as she reaches the pinnacle of her true self, yet she is left with white hair as a reminder of the lesson she learned. These two movies illustrate that the experience of growing older can contain as much magic as the lives of children shown in films such as Totoro.

Even with the intricate messages and profound themes that populate the work of Studio Ghibli, many casual fans continue to categorize the films as children’s media not worthy of critical analysis or viewing by a grown audience. This is indicative of a larger issue regarding serious or darker works being more highly praised than those with more hopeful, uplifting messages. This may cause the audiences to undervalue storylines such as those in Studio Ghibli films.

The truth is, we all need hope. In a world which is often so devoid of any “good” news, we can look to storylines in which characters can eventually create a beautiful life for themselves. As Hayao Miyazaki said upon the release of Howl’s Moving Castle, “even amidst the hatred and carnage, life is still worth living. It is possible for wonderful encounters and beautiful things to exist.” This message encapsulates the philosophy captured within Studio Ghibli films. It is one people of all ages can take to heart.